- Home

- Gail Gauthier

Happy Kid! Page 6

Happy Kid! Read online

Page 6

But that meant the only review work I had left was the most important. Not that I cared that much about getting ready for the yearly SSASies. I’d always done really well on them, and I didn’t want to mess with success by going overboard studying. I could end up making things a whole lot worse doing something like that.

No, the review work I had left, the “Are We Alone?” essay for Mr. Borden, was important because Chelsea was in his class. I had spent all of sixth grade sitting in two classes with her. Maybe I could spend all of seventh grade making a good impression on her. Then, when we were together next year in those ninth-grade English and social studies classes, we could talk on the phone a few times. And then when we were together in whatever kind of A-kid courses they had at the high school, we could spend all our time between classes together. Then in eleventh grade . . . I’d have someone to go with me to the Junior Prom!

So I sat down at the crummy old computer I had inherited when my grandmother upgraded hers, which is all I have in my room because my parents insist it’s just fine for doing homework. I opened a new file and typed “Are We Alone?” at the top of the screen. Then I typed “No.”

I deleted the “No” and started again.

Are We Alone?

Some people ask, Are we alone? The answer is no.

Well, there’s one paragraph, I thought. Then I went on.

Are We Alone?

Some people ask, Are we alone? The answer is no.

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines “alone” as “separated from others,” “isolated,” “exclusive of anything or anyone else.”

Uh-oh, I thought as I closed the dictionary and dropped it on the floor. That means the answer is yes.

Are We Alone?

Some people ask, Are we alone? The answer is yes.

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines alone as “separated from others,” “isolated,” “exclusive of anything or anyone else.” Even if there are aliens in the universe, we are separate from them and isolated, and so we are alone.

I thought that sounded really intelligent and deep, as if I spent a lot of time thinking, which is exactly how A-kid papers sound.

Then I kind of drew a blank.

I sat at my desk and kicked at some stuff on my floor while I tried to think. I hit something that was hidden under my pajama bottoms. I kept kicking and thinking and kicking and thinking. After a while, I was kicking and not thinking and kicking and not thinking. I don’t know how long I went on like that before I finally looked down and saw that what I had been kicking was the copy of Happy Kid! I’d thrown on the floor that morning after I’d finished with it.

Since work on my essay had come to a halt, I thought I’d put my time to good use by reading another chapter. I didn’t have to do anything the book told me to, after all. I could just read a chapter and get a dollar. So I opened up Happy Kid! and once again started to read the first thing I found.

Does Your Life Stink or Is It YOU?

Say you wake up to a beautiful day and spend it being miserable because you have to go to school. Or you get a B-minus on a paper and wish it were an A. Or you have an opportunity to eat lunch with a friend and all you can think about is how bummed out you are because the friend is spending time with someone else later. You could be one of those people who only see the worst in every situation. Think about it. Does your life actually stink, or do you just think it does?

I had to laugh when I read that. Just how is a person supposed to be able to tell if his life stinks or he just thinks it does? And couldn’t you turn that question around? “Is your life really great or do you just think it is?” I thought I’d like to hear a happy person answer that.

What I should have been feeling was surprise that I just happened to stumble upon this passage that just happened to be about the exact thing my mother just happened to have been nagging me about for days. But she had bought me the book, after all, so I never gave it a thought.

CHAPTER 6

You can never find a bookmark when you want one, at least not in my room, so I left Happy Kid! open facedown on the floor for a couple of days to mark my place. I must have broken the rigid binding when I left it on the floor, because the next few times I tried to read a new chapter and make a dollar, it opened up to the same place. “Does Your Life Stink or Is It YOU?” The rest of the book was as stiff as it had ever been, though, because when I tried to intentionally open it to a new page, I couldn’t keep it open long enough to finish reading what was there. As soon as I moved my hands from the sides of the book so I could read what was under them, the pages started flipping and the first thing I knew, there I was again at “Does Your Life Stink or Is It YOU?”

I started becoming very self-conscious about using deodorant.

I was finally able to open the book to a new chapter the next Monday morning. Unfortunately, the new chapter was a lot like the one I’d been reading over and over again. I just had time to complain to my mother and collect a dollar from her before I had to leave the house.

I had to go to the orthodontist. With my grandmother. She owns a real estate agency and can take time off much more easily than either of my parents. That’s why I end up spending way too much time with her.

“This morning I’m missing math so I can go to the orthodontist. Is that a good thing because I hate math, or is it a bad thing because I’m terrible at it, so I really ought to be in class learning all I can?”

“You lost me,” Nana replied.

I pulled Happy Kid! out of my backpack and it fell open in my hand.

“Would you look at this?” I said. “Last week this book kept opening up to the same spot because I wrecked its binding. This morning I finally got it to open to something new, and now it just opened up to that same place again. There must be something wrong with this thing.”

“I’m still lost,” Nana said.

“I can explain everything. I brought this book with me to read in the doctor’s office because Mom said she’d give me a dollar for every chapter I finish. The chapters are really short, by the way, so it’s not a big deal. Here’s the chapter I read this morning while I was waiting for you to pick me up.”

Make Sure You’re Getting the Real Picture!

The first step in solving that negativity problem is recognizing it exists. Make a list of all the times you look for the worst in life and find it. Are the items on your list really the worst? Or do you just think they are because that’s what you were looking for?

“You’re not trying to suggest that I have a negativity problem, are you?” Nana asked. “I get enough of that kind of thing from your mother, thank you very much.”

“I get that from her, too! She says I look for the worst in every situation. That’s why she got me this book. She thinks it will make me happy.”

Nana and I both laughed.

“The last chapter I read says that if you’re one of those people who does see the worst in every situation, then your life really isn’t all that bad, you just think it is. So it would actually be a good thing if we’re negative. Can you believe it? That would mean that our lives are good, we just don’t know it.”

“Really?” Nana said. “Be sure to explain that to your mom.”

“The thing is, I couldn’t figure out how to tell if something’s actually bad or if I just think it is. Then this morning I opened this book up and found this chapter I just read you that explains how to do it. Make a list.”

“So this is what you’ve been spending your time thinking about, huh?” Nana asked as she turned into Dr. Allegretti’s parking lot.

“This and how I can get my homework done faster so I can take taekwondo,” I said.

“Taekwondo?” she repeated as she parked the car. “Good for you, Kyle! In this day and age, we all have to be prepared to defend our way of life.”

Defend our way of life? I thought. Wasn’t she talking about fighting terrorists? I just wanted to get to know a girl.

O

nce we were in Dr. Allegretti’s office, I let my grandmother have the only seat left. It was on the couch between the bald man with the purple splotch on his head and the woman who kept apologizing because the baby she was holding smelled. I sat on the floor, pulled a piece of paper out of my backpack, and wrote “Things I Think Are Bad That Are Really Good.”

When I left the office forty minutes later, the wire that went through the brackets on my lower teeth had been pulled so tight that tears had come to my eyes. And there was nothing on my list.

I didn’t realize I’d left my backpack in Nana’s car until I got to the school office so I could get my late pass. The thing weighs nearly thirty pounds. How could I not have noticed I wasn’t carrying it? Of course, my mother’s note explaining why I was late was in the backpack.

I was trying to tell the secretary what had happened when someone behind her shouted, “Yo! Kyle!”

I looked over the secretary’s shoulder and there was Jake standing next to the principal, Mr. Alldredge.

“Gus, can’t we do something to help out my man Kyle?” Jake said to Mr. Alldredge.

Gus? I thought as Mr. Alldredge snapped “In there” at Jake and pointed toward the door to his office.

“Hey, I tried,” Jake called to me as he went in.

Mr. Alldredge stepped over to the attendance window. “You’re Jake Rogers’s man now, are you?” he asked.Though it wasn’t really a question. It was more of an accusation.

“He—not—I—no,” I stammered.

Mr. Alldredge shook his head in disgust, and the secretary handed me an unexcused late pass, meaning that if I didn’t bring a note the next day, my first two period teachers didn’t have to let me make up whatever work I’d missed.

That didn’t make the list.

I got into social studies halfway through the class, which meant that everybody looked at me as I walked through the door. I waved my bright red unexcused late pass in Ms. Cannon’s direction.

“My homework is in my backpack and my backpack is in my grandmother’s car, and my mouth hurts because I went to the orthodontist,” I said as I slowly slid into my seat.

I hoped Chelsea noticed how much I was suffering.

“Do you know what would happen if I used that excuse at the university where I’m working on my Ph.D.?” Ms. Cannon asked me.

During the first week of school Ms. Cannon had managed to mention her Ph.D. nearly every day.

“You don’t have braces, Ms. Cannon. No one would believe you had been to the orthodontist,” I pointed out.

“You missed my point, Kyle. You have to pay attention to what you’re doing. Tomorrow we’ll have been in school just one week, and already you’re leaving your things all over the place. For that matter, did you really have to schedule a doctor’s appointment during school hours?”

By the time I got out of social studies class, I still had nothing on my list. Everything I thought was bad really was. If I’d been keeping a list called “Proof That Life Sucks,” it would have been filling right up.

I was late getting out of class, so I was stuck walking to English by myself.

Anytime you’re with someone at school, particularly someone you actually like or can at least get along with, it’s an accident. Even in the hallways you might not see your friends if their schedules are a lot different than yours. So the halls at school are filled with people by themselves or pretending they’re not by themselves, or, if they really are with other people, being loud about it like Jamie and Beth so that everyone will know they’re not alone.

Why didn’t I think of this being-by-yourself stuff last week while I was writing my “Are We Alone?” essay? I wondered. Talk about something that sounded intelligent and deep.

I saw Chelsea’s head above the crowd up ahead of me. I would have liked to have gotten a little closer to her, maybe almost walked together, but I couldn’t get past Jamie and Beth, who were squealing with Melissa about a note one of them had written.

I got to English and waited for Mr. Borden to ask us to turn in our homework, when the whole sad story of my backpack, my grandmother, and my trip to the orthodontist would have to be told again. But he didn’t. Instead, he handed back the essays we’d turned in on Friday and announced that we were going to share them.

Was having to “share” my essay a good thing that I wasn’t recognizing because I had a problem with negative thinking? No way.

“We’re going to tear your essays apart in class so you can identify your writing weaknesses,” Mr. Borden explained. “In the weeks to come we’ll study classic essayists so you can see how writing should be done. I will not teach you to write. The masters will.”

This speech got a lot of the A-kids all fired up. A lot of them love doing whatever the teachers want to do. I don’t mean they’re suck-ups like Melissa. I mean they’ve been brainwashed or something. They always want to do what the teacher wants to do and to think what the teacher thinks. I don’t understand it. For instance, I tried to tell myself that it was really good that I was going to be studying classic essayists and learning something from the masters, whoever they were. But I couldn’t help thinking that the word “classic” is almost always bad news unless you’re talking about old movies. I bet the A-kids never gave that a thought.

Melissa read first because, basically, she’s a show-off and loves the sound of her own voice. She read something very fancy about how much it hurt to stand under the stars at night and to see so many of them while there is only one of her. Personally, I think it’s a very good thing that there’s only one of her.

One of the other kids in the class said that Melissa hadn’t written an essay, she’d written a poem. I had totally missed that because, though Melissa is always writing things she says are poetry, they never rhyme, so I have to take her word for it. Teachers, though, love poetry that doesn’t rhyme. They can’t get enough of the stuff. Sure enough, Mr. Borden said what Melissa had written was an okay poem. She grinned all over, anyway, and wriggled around in her seat from all the attention. I didn’t gag, even though I wanted to.

“But that poem would get you very little credit with the people who score the SSASies,” Mr. Borden went on.

The room went totally still. Melissa looked as if she’d been turned to stone.

“You know why? Because they’re all hired hacks making minimum wage. You think scholars, trained critics, read these essays? Hell, no! They’re all old ladies trying to supplement their Social Security checks or kids out of college who can’t get jobs. They won’t recognize a quality piece of writing like this. They’re looking for something short and easy to understand—something a machine could score in seconds, the way a machine, in just seconds, scores the bubble-test portion of the SSASies.”

Aha! I thought. That explains why I always do well on the SSASies. My writing samples are always as short as I can make them. And since I never use metaphors and not even many adjectives, what’s not to understand?

The next reader began her essay with “As I walk through the hallways at school, I am surrounded by hundreds of people, and yet I am alone. No one is like me.”

I couldn’t believe it! I was listening to my essay! The essay I would have written if I’d thought of it while I was doing my homework instead of in the hall on my way to class.

Except it was written by . . . Chelsea.

She went on about the hallway being a world and the people in it being different countries. She said it was as if each person was a separate culture with a separate language that no one else spoke. Then she got into all this stuff about words being like ambassadors and how communication could bring all the countries in the hallway together just as it could bring all the countries in the real world together.

I definitely would never have said any of that because I wouldn’t have thought of it in a hundred years. But we did both think about hallways.

Mr. Borden and the other kids in the class said her imagery was “unique,” she had used an “extended meta

phor,” and she understood the essay format.

“That was really good,” I said after everyone else was through talking. I thought contributing to the class discussion would make a good impression on Chelsea, especially since my contribution was all about her. My reward was to have Mr. Borden tell me that I should read next.

Are We Alone?

Some people ask, Are we alone? The answer is yes.

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines alone as “separated from others,” “isolated,” “exclusive of anything or anyone else.” Even if there are aliens in the universe, we are separate from them and isolated and so we are alone.

Say there is life on another planet. Say there is life on lots of other planets. What does it have to do with us? Do we see any of these other beings? Do we communicate with them? Do we exchange goods and services?

Scientists who spend millions of dollars searching the skies for signs of life believe that just finding some tiny signal that there are other intelligent beings would provide the human race with companionship. But would it? How would knowing that there are others on other planets who we can’t talk with, see, or hear make us feel that we have companions in this universe? It would be just like posting a message at an on-line forum. You know there are other people there because you see their messages. But they never respond to yours. So just knowing that there are others there doesn’t make you feel good. You just feel worse than ever because you can’t communicate with them.

Are we alone? Definitely.

If I had known I was going to have to read the essay aloud, particularly in front of Chelsea, I would never have included the part about people in forums not writing back to me. Not that that ever actually happened. Well, just once.

The rest of the class didn’t mention the forums, though. They were too busy talking about my poor topic sentences and lack of transitions between paragraphs. They said that even though I restated my thesis in my conclusion, as I was supposed to, it still stunk. One kid thought I sounded depressed and should go see somebody.

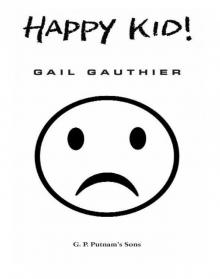

Happy Kid!

Happy Kid!